I have just completed my second week here at SFH. As you probably gathered from my last post – life is crazy here and very busy! My days are lasting from 7.30am to around 6pm at night so there is too much to tell! So, I thought this week I would focus on telling you what has been happening on the paediatric ward.

This week I had the opportunity to work in both the SCBU (Special Care Baby Unit) and in the malnutrition section of the ward in particular. SCBU looks after new-borns who are having problems in the period after birth. Largely we see premature babies, neonatal sepsis and birth asphyxia.

This week I had the opportunity to work in both the SCBU (Special Care Baby Unit) and in the malnutrition section of the ward in particular. SCBU looks after new-borns who are having problems in the period after birth. Largely we see premature babies, neonatal sepsis and birth asphyxia.

Luckily, this week has seen the arrival of Nigel – a recently retired UK paediatrician who has been coming to St Francis for 3 years doing 3 month attachments. He brings great experience to the paediatric team and also knows many of the staff.

The babies of SCBU have won over my heart this week. They are far too cute although tiny and vulnerable. The smallest patient we have at the moment weighs 980g! But I think this is making working in SCBU very hard as it is tough to see them struggling for life and knowing that we only have the bare basics of equipment.

Our incubators are literally white wooden boxes with a light bulb set over a dish of water for heating (and moisture). While this works and helps to keep them warm, there is none of the monitoring we would have at home. Unfortunately a huge problem here is seizures and apnoea’s (where the baby stops breathing).

Without stimulation/touch some of these babies die from repeated episodes of progressively worsening apnoea. As there is limited nursing staff and the mothers cannot stay with their babies, often these episodes go unnoticed and mortality can be high.

Without stimulation/touch some of these babies die from repeated episodes of progressively worsening apnoea. As there is limited nursing staff and the mothers cannot stay with their babies, often these episodes go unnoticed and mortality can be high.

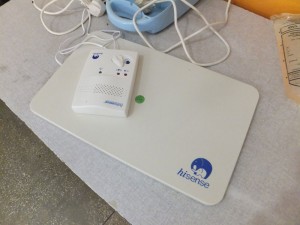

In an attempt to overcome this problem, Dr Nigel and his wife fundraised for special baby apnoea alarms and brought them out from the UK last year. These are special mats that sense movement (e.g. chest movement) and if the babies movement ceases for >10 seconds) an alarm will sound to alert the nurses.

I thought this was absolutely wonderful and just the simple sort of system that would save lives. Dr Nigel also provided rechargeable batteries (and charger) so that there would be no barrier to their use within the hospital setting. However, it was disheartening to find out that soon after Dr Nigel had left a year ago, they were put away in a box and haven’t been utilised! It wasn’t until he returned this week and asked after them that they were ‘rediscovered’.

I think in some ways they were considered “hard work” to use (especially when you can get false alarms) and unfortunately many of the mothers did not want to use them. We have encountered problems this week convincing sceptical mothers of the benefits and teaching them to use the alarm (as it requires their buy in to turn the alarm on/off before and after handling the baby) especially when translating through sceptical staff!

It is interesting to wonder why this might be happening? Is it a distrust of “white doctors”, a distrust of very unfamiliar technology, a lack of education and poor communication from us or a belief that it just isn’t needed? However, after a few successful saves this week, we have begun to make progress and perhaps change some minds!

It is interesting to wonder why this might be happening? Is it a distrust of “white doctors”, a distrust of very unfamiliar technology, a lack of education and poor communication from us or a belief that it just isn’t needed? However, after a few successful saves this week, we have begun to make progress and perhaps change some minds!

Despite the challenges of SCBU, I cannot begin to tell you how awful it is to walk into the malnutrition ward. To see children suffering for the sake of a lack of nutrition is just devastating. Some children are so thin that I can literally count every rib, and feel as though I will break them by lifting them.

Others are swollen (the typical World Vision picture of African children with large stomachs) and their skin is literally peeling off. I knew coming to Africa and choosing to paediatrics that I would see sights like this.

But nothing can really prepare you. Nothing can prepare you to see the misery in their eyes or listen to their whimpering. Many are simply just too weak and tired to cry. It truly breaks my heart to see this. One thing that really did get to me this week was seeing one child at 18 months of age who weighed less than I did at birth. How, how can that happen?

Severe malnutrition is unfortunately a common diagnosis here. Its incidence can peak at various times of the year dependent on families’ income. Usually the incidence, I am told, decreases in the time surrounding harvesting, where farmers can sell their crops and thus have an income. However later, this money begins to run short and thus so too does nutritious food. And unfortunately it is the young who are hit the hardest.

Severe malnutrition is unfortunately a common diagnosis here. Its incidence can peak at various times of the year dependent on families’ income. Usually the incidence, I am told, decreases in the time surrounding harvesting, where farmers can sell their crops and thus have an income. However later, this money begins to run short and thus so too does nutritious food. And unfortunately it is the young who are hit the hardest.

HIV/Aids also rears its ugly head in causing malnutrition here. Unfortunately, HIV does continue to claim the lives of young Zambians including young mothers. Without the supply of breast milk for her young child, this child is a high risk of developing malnutrition.

Another problem has been a cultural one surrounding food. In Zambia, one of the staple meals is that of Nshima – a white dough like substance made from maize. It is eaten with a side of beans or occasionally meat.

If a child is hungry, usually they are given more Nshima as it is very filling (although personally I found it very bland!). However, Nshima holds little nutritional value and children are missing the protein that comes from other sources such as nuts, and meat.

Without a steady/stable intake of protein, the body becomes very malnourished rather quickly. The government is trying to promote the use of ground nuts mixed into the Nshima to try and battle this problem. Furthermore the problem has been noted even closer to home. It has been said that our patients here in the hospital do not receive enough calories in the hospital meals to sustain a normal adult!

Without a steady/stable intake of protein, the body becomes very malnourished rather quickly. The government is trying to promote the use of ground nuts mixed into the Nshima to try and battle this problem. Furthermore the problem has been noted even closer to home. It has been said that our patients here in the hospital do not receive enough calories in the hospital meals to sustain a normal adult!

There are so many things that are impacting on the health of this population and it is obvious that despite efforts to combat malnutrition perhaps the message isn’t getting to the at-risk people or focussing on the right problems!

Unfortunately the children we see often come in very late and are at the severe end of malnutrition (often 3-4 standard deviations below the mean). There is a 30% mortality rate for children in our malnutrition bays – 3 out of every 10 children will not make it home. There is only so much you can do in the face of the extreme illness that accompanies malnutrition.

So, I suppose this week has been an introduction to what the smallest and most vulnerable Zambians are faced with. It has been a big learning curve for me. From dealing with the emotions evoked from dealing with the young to the physiology of the effects of malnutrition and how to treat it. I can’t begin to tell you all how this experience is changing me!

No comments yet.

Leave a comment