We were out of time to see more of Anuradhapura, but my friend had invited me to visit his village, and I’d jumped at the chance to see another side of Sri Lanka beyond the bustle of busy Colombo. Rajanganaya was a short trip away by car, and Kasun’s family welcomed me in. I got a motorbike tour of the township and his local clinic, and started working on my Sinhala. I’ve picked up a few bits and bobs: ස්තුතියි (stūtiyi, thank you), මොකක්ද? (mokakda?, what is it?), ඇයි hospital එකට ආවේ? (æyi hospital ekaṭa āvē?, Why [did you] come to [this] hospital?). I’m trying to pick up some basic Tamil phrases, too (வணக்கம்! Vaṇakkam! Hello!). There’s really not enough time to work on language skills to any functional level, so I’m just getting what I can as I go. Luckily, the doctors all speak English.

Visiting Rajanganaya village, I was struck by its quietness and darkness. The forest is a world apart from Colombo. I asked around to try to understand how medicine changed out here. Most people here farm, and snakebites are of the most dangerous risks. Russell’s vipers and Sri Lankan kraits love to weave through plantations or into houses at night, and are viciously cardio- and neurotoxic. Getting to antivenin in time can be difficult, and many people do lose their lives to snakebite. On our tour around, Kasun pointed out to me the yellow oleander plant, an important toxicology case to know. The seeds are swiftly cardiotoxic and taken commonly as a suicide agent. Thankfully, despite coming across some termite mounds the snakes like to sleep in, we didn’t see any snakes this time. People here work extremely hard, physical labour jobs in an unforgiving environment, and to make the jump to a profession in the big city is undoubtedly competitive for the local students. And yet, it is certainly nice to not be woken up by motorbikes at night. I can see why people would be drawn back to this rural life, too.

Thanks to Kasun’s role as a trainee doctor at the local clinic, I’ve been able to spend an afternoon at the village clinic seeing patients, too. So much for a weekend off! In truth, I was thrilled to get a look at the rural hospital. Even though New Zealand is very developed, we have regions with reduced access to resources, and the benefits of improving your foundational skills are obvious. The clinic was overstretched, and staff lack access to any form of imaging or even the most basic of blood tests like full blood counts. It’s undoubtable that you would need to develop both a strong confidence in your clinical diagnostic skills, and a great deal of comfort with unavoidable uncertainty.

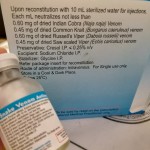

I was given a tour of the pharmacy, which despite its limitations had every essential drug I could think of, and got to review some patient charts and notes, too. One big prescribing difference: everyone, and I mean everyone, seems to be on theophylline. This respiratory drug that opens up the airways is one I was taught to be a bit cautious of, with its bevvy of side effects and tendency to change up its concentrations on you. I trust the doctors here though, so I don’t know that these are errors as much as they are differences of practice. I’ve heard before about how doctors working overseas can get into ugly battles over who’s medical opinion is most correct, and can see how these sorts of treatment decisions require a lot of context about the local population’s health risks that I don’t have, either. One great example hung on the walls next to me – a promotional poster for a synthetic, healthier betel nut substitute supported by the government. Betel nut, totally absent in Western countries, is a staple in much of Asia as a tobacco-like stimulant that is chewed and expectorated in a red clump. It has the unhelpful bonus of giving you oral cancer in the process.

A last trip around a few sites here, and my long weekend has come to a close. I made a thank-you meal for Kasun’s extended family from around the village, patched together from the Western international aisle in a supermarket that was filled primarily with things I have never seen before. It was certainly pasta of some description, I would say. No knives and forks, so we ate pasta with our bare hands, which was somehow much weirder than eating Sri Lankan food like this. It managed to go down well and despite the having a roomful of people, I managed to stuff them all. The neighbours even carted off the extra. A good sign!

It’s time to get back into the clinical world proper. I’m pensive about the upcoming week in Colombo. Surgery doesn’t come to me as easily as things I can sit and think about, and is famously unforgiving for those that can’t keep up. Jumping into it is why I’m here, though. I scrolled through the textbook I’d copied onto my phone on the night bus ride home until I fell asleep. At least, until I tried to fall asleep. The bus driver decided to keep himself alert by blasting Bollywood music videos the entire ride home, which became a lot less catchy at 4 am. This must be what they mean by dukkha.

No comments yet.

Leave a comment