My time in Guatamala is coming to an end now; my Spanish has improved, I have become part of the local football team and my days at the medical centre have been varied and very different from New Zealand.

Each day brings something new. Most days I take consultations, examine the patient and provide basic treatment where necessary.

The presentations vary from a basic cold to a high fever and last week I had to suture up a toe cut by a machete. Many infectious diseases such as malaria, dengue and chikungunya must be in the differential diagnosis. The centre takes care of all the basic needs of the community, including following pregnant women as well as monitoring growth and health of the children. Family planning is an important part of the medical provision here as many families consist of 12 children or more, and girls marry as young as 12 years of age. Once a year, there is a team of a gynaecologist and supporting staff to provide alternative measures of contraception including surgery, jadelle subcutaneous implants and intrauterine implants. This year, this fell in April and I had the privilege of assisting. The most common method used regularly however, are hormonal injections.

There are no doctors here; the service is provided only by nurses, and treatment is generally regimented according to local guidelines. It makes sense and is important to have such guidelines, but at times, they can be frustrating and restrict alternative treatment that would otherwise be more useful. However, more than the limited knowledge of the local staff, the limited resources here are even more restricting.

Some days I accompany a nurse on home visits, travelling with the nurse by motorbike to the homes of postpartum women. This involves removal of sutures, general check up of the neonate and the mother, as well as provision of vitamins and general advice. Some women choose to birth at home, while others have been rushed to nearby Fray Hospital for an emergency Caesarean section. Many have not sought medical attention after birth and therefore vaccinations and other follow up care of the neonate are required. A typical home here consists of a single room, with a thatched roof and a dirt floor. There is a fire in the centre where the cooking is done, and beds, or hammocks line the walls. The toilet is a hole in the ground outside in a small ‘hut’. There are a number of health risks to the mother and baby. This includes the health danger of an open fire within the home, which means the neonate is breathing in smoky air as well as the danger associated with the baby swaddled in blankets in a hot climate, lying in a hammock, where the head is not lying flat. On top of this is the lack of hygiene. There is no free access to clean water and therefore gastrointestinal disease and parasites are rampant. There are animals wandering around the home; a large family of ducks or chickens, and dogs that come and go as they please. There are pigs wandering in the backyard and the road beside the home lifts dust, entering the lungs of the inhabitants.

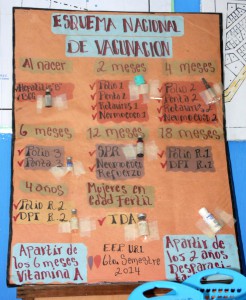

There is a great vaccination programme here and all the children born here are documented with a local register of the vaccinations that have already been provided. If a family does not bring in their child to be vaccinated, they are visited in their home to provide these accordingly. There has also been a programme established for deparasitation. Parasites are a major problem here and preventative treatment at a young age can help prevent much disease. This is included in the home visits.

All medical treatment in Guatemala is provided for free, so cost is not a barrier to access health care. This includes the home visits as well as vaccination programmes. However, although cost is not an major issue, I have recognised that a major barrier to health care is the lack of health literacy. The importance of health education in the prevention of disease is striking. There have been a number of afternoons I have spent at the medical centre here feeling somewhat frustrated by my limitation in the ability to help. I spend much of my day dealing with secondary problems, and with the medical provisions we have, I can only offer temporary symptomatic relief. What is really needed is education on how to prevent such diseases. This is a benefit of the home visits as it provides a great opportunity to provide education.

Before I arrived, I was asked in advance to provide a first aid presentation to the girls at the school. My initial thought was that this consisted of education around CPR, dealing with burns and other acute emergencies. However I have quickly realised that more importantly, this presentation needs to consist of information on the importance of more basic principles of health such as washing hands, cleaning teeth and diet. Many people here don’t understand the importance of personal hygiene. The presentation of this lack of hygiene has been at times, extreme. One Monday morning, I arrived to the medical centre to find a mother with her baby already there. She had travelled a long way from her home town and her baby, only 3 months, was completely covered in bites, scratches and crawling insects and flies were buzzing around the head. We sent her and her child immediately to the hospital, while providing the rest of the family with treatment for scabies and skin infections and provided some education on the importance of washing. Dental hygiene is also significantly lacking. Young children already have rotting teeth and many young adults have very few teeth, if any, remaining. I could not say how many might even own a toothbrush here, but it is certainly not a priority. The diet of fizzy drinks and sugary snacks doesn’t help. ‘Agua’ here refers to any type of fizzy drink or sweet drink; if you want water, you must specify ‘agua pura’.

During my time here, I have begun to develop ideas on how to help. I have been working with the girls at the school to produce educational posters to display at the school and the medical centre, translated in both Q’eqch’í and Spanish. Along with the help of a friend who studied design, and the girls at the school to help translate into the local language, I have been able to create posters, as well as laminated educational pamphlets about how to wash hands, body and teeth. Alongside this, I have purchased and supplied the centre with several hygiene supplies including toothbrushes, toothpaste, soap and shampoo. I have also recognised a number of gaps in the medical resources here including a foetal Doppler ultrasound, which was raised as a need by the local staff. Thanks to the provision of the Pat Farry Scholarship I was able to fund and provide these. Additionally I have been kindly donated a couple of glucometers to supply the medical centre.

I am really pleased that I allocated my whole elective to this village. My decision to do this was to allow time to form relationships, learn the culture and the language, and hopefully make long lasting connections. The longer I spend here, the more needs I recognise, and the greater my desire to contribute and make a difference. However a lot of these things take time; it takes time to identify the needs, to develop ideas and to test these ideas. In addition it takes time to form trust and develop respect from those in the community.

I am enjoying the fact that I have had time to invest and contribute to the community. It is a challenging environment and I hope I will leave some positive changes behind. However, just as importantly, I have learnt yet again to appreciate the privileges we have in New Zealand and hopefully return with a new perspective on our medical system.

1 Comment to 'A day at the medical centre'

May 16, 2019

What an awesome experience!

Leave a comment